The traumatic loss of a dear uncle when I was seven; he was stabbed to death abroad, and watching from a young age the pain on my family's faces... My mum, who had lost a beloved brother, my granny her son. The pain that followed and my own fear of trying to understand that he was gone... forever, gone!

Young children can often be shielded from the severity of such death, like being in a room where the television is turned on and you hear it in the background. Or perhaps you overhear a parent talking to a friend about ‘how such and such was killed in an accident’. Then you move on, not really ever understanding the enormity of the situation.

But, for me at seven, this was BIG. HUGE.

What was the hugest part for me was seeing those I loved the most, in completely earth-shattering despair. The pain was everywhere. It wasn’t something that could have been hidden, even if the parents or grandparents had tried (which I am certain they did hide some, or most, of their agony), but nonetheless it was everywhere.

Like a thick feeling in the air. An unsafe feeling. Was someone crying again? What was I meant to do to be able to understand this.

It is often at these times as we witness our parents grieve and see them so fragile, that it is a powerful emotion to fear.

Other losses in my early years - possibly more expected, grand-parents, great uncles or aunts. Also, as I entered my teens, a friend in a car accident and another from cancer. All creating a growing pain inside, a question of why is there pain in this way?

THE BIG ONE

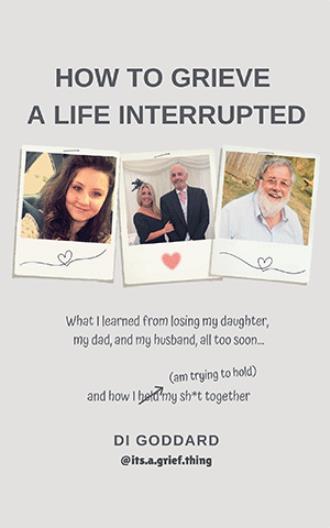

My 'biggest' (completely f*cking enormous) personal loss was in 2015, when my eldest daughter Liana passed away aged 22, after fighting multi-organ failure for 4.5yrs. She was on a gap-year in Uganda when her pancreas and kidneys failed and she was medically evacuated out of the country to Nairobi, Kenya, where her life was saved, for now.

We met her there, and after two weeks in ICU she was transferred back to the UK (I love how clean that sentence sounds… instead of the brutal reality of being taken into an office and being told she will not likely live, that decisions needed to be made, that even if she did survive, her life would be altered, forever).

Once back in the UK (and yes, none of us knew how we made it back) Liana spent the next 18 months having endless treatment and operations, dialysis, bouts of agonising pancreatitis. Moving up the hospital seriousness scale (Dorchester, Yeovil, Bristol no.1, Bristol no.2, UCLH London, The Royal Free, London) where the operation that couldn’t be done, was done anyway. My husband Jason and I sat in the corridors for 16hrs until she finally reached ICU having had a Longitudinal Pancreaticojejunostomy and Liver bile duct transplant.

She went into it knowing she would probably not survive, but she came out of it alive!

This was just one of the operations, as they had tried everything they could towards getting her well enough for a kidney transplant; they had completely shut down on day one, and there was no rain dance (we did them all) that made them wake up again.

Liana hated dialysis. I don’t like the word ‘hate’ – it is a strong and powerful word that depicts so much ugliness… but, be sure, she HATED dialysis.

Begging God in a non-religious way for a transplant daily.

That transplant came in January 2014, when she was 21. What we believed was the end (of waiting and pain and dialysis) was just the beginning…. Hadn’t even thought past what would happen if she did actually get a new kidney.

I recall the journey home from the hospital at 4am with Jason and Caitlin, my younger daughter, and just suddenly crying at the realisation that now we had stepped into a whole new level of ‘what-if’s’… What if she rejected the organ, what if the immunosuppressants meant she couldn’t fight off an infection?

This pre- Covid era of wearing a mask when you went near her in hospital was pretty freaky.

So, elatedly, she got her life back… her joy was immeasurable, her life a wonderful sense of opportunity again, until she lost it, until she literally lost her life because of it.

Sadly, ten months after her transplant, she experienced complications and rejection of her kidney and to keep it alive, and her off dialysis (remember how much she HATED that one) she had to have a change of immunosuppressants, rapidly, in hospital care.

This caused her immune system to be completely wiped out, as was expected. What is always hoped won’t happen, and not needed, is that during that time in hospital, she caught a virus called CMV cytomegalovirus, quite a common virus really, and a few weeks later it went to her lungs.

I Googled it… Stupidly I Googled it…

CMV pneumonitis in immunocompromised patients is fatal, I read online. It was fatal…

The journey for her and us was harrowing; the constant pain and ill-health, the inevitability of what would come in an untimely manner for her, and although she was ultimately at peace with that, I wasn't.

After two weeks of deteriorating lungs, she went onto life-support for the last time. She wasn’t scared of death, only of pain.

As she drifted off to sleep, I panicked at the thought I may not get the chance to tell her anything ever again, so I called out to her ‘I love you, I love you, I love you’… Her last words to me as she fell into a medically induced coma were, ‘I love you, Mum’.

The decision to switch her life-support off two weeks later as she got sicker and didn’t respond to any treatment was harrowing, as was the loss we felt. People always say there is no way to explain the grief, that it is so unnatural for a parent to lose their child, yet it still happens.

I sat in a bubble of disbelief, of indescribable pain, of utter chaos, as my life seemed to unravel right there and then in that moment.

It is true that you forget, or block out many things, but never the most painful things. I don't remember who attended her funeral, but I remember the hollow pain digging deep inside every muscle, nerve and fibre of my being, as I hoped it wasn't true…

I just had to try and remember to breathe, and even that seemed hard.