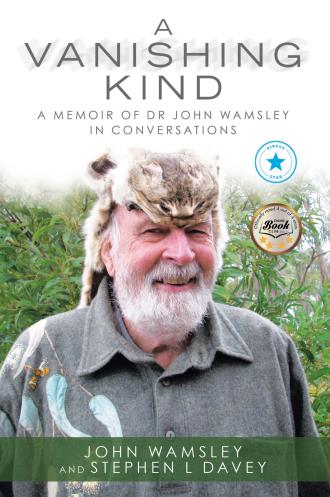

Into that very formally dressed gathering of people who came from all over Australia for the awards ceremony, there intruded a six foot two inch, broad shouldered man with his partner by his side. On his head, and flowing down his back in a carpet of lynx-like markings, was the pelt of a very large cat.

Its disembodied face stared from sightless eyes and the directional ears were still. Not a wild species, but a huge specimen of Felis cattus, the domestic cat gone feral. John’s own heavily bearded face perfectly complimented the feline headgear. Indeed, the two entities, the cat and the man, appeared almost of a kind.

The gathered throng truly didn’t know where to look. Their priceless expressions are captured for posterity on video. Such an image had never been seen before in all the western world. It would forever define the man, John Wamsley, in the eyes of all who subsequently heard his name.

Today, three decades on, if I mention John’s name and people do not immediately react, I only have to say, ‘You know, the man in the cat-hat,’ and most people then get who I mean.

The reaction was immediate and intense. John jokingly says that he knew where the news got to in the world by where the death threats were coming from. But the death threats really came.

John says, ‘A photograph appeared on the front page of the Adelaide Advertiser. It made every major newspaper in Australia. It enraged Australia. It enraged the world. The education lesson had commenced. On the day it appeared on the front page of the Advertiser, the various environment ministers were meeting in Adelaide. Cats were suddenly on the agenda. The timing could not have been better.

‘I received hundreds of death threats. Animal Liberation ran a massive campaign to stop people visiting our sanctuaries. Television discovered the cat-hat. It went round the world. The story grew more bizarre at each telling. It was soon joined with cat recipes etc. Everyone wanted a cat-hat. Warrawong Sanctuary sold hundreds of them. Ironically, visitor numbers fell markedly during this time. There was more sympathy for cats than for wildlife.

‘Yet with each telling a little could be said about the damage done by cats. Slowly, very slowly, the message began to get through. This was more than just a publicity stunt. This was serious conservation. Within a few years every state in Australia would pass legislation on cats.

‘The demand for “cat hats” was enormous. We were offering $35 per tanned full cat skin. We were selling cat hats for $50 each and couldn’t get enough to meet the demand. We sold thousands. Our cat traps were selling nearly as well.

‘I even talked of the concept of writing a cat recipe book. The public loved it. They couldn’t get enough. All their lives they had submitted to the continual torment of indecent neighbours letting their cats run amok. Now was the time for revenge.

‘There is no doubt, in my mind, that the biggest problem our wildlife faces is from domestic cat owners. Not because domestic cats destroy wildlife but because their owners destroy wildlife projects. Gradually, it all turned around. Cat owners even began to look a little embarrassed when they admitted they owned a cat. Some began to talk of “responsible cat ownership.”

‘The new law in South Australia was very clear. Any cat on a national Park or Sanctuary could be destroyed by an authorised person.’

Under the SA dog and cat management act, ‘Any unidentified cat (i.e. feral cat) can be seized, detained, destroyed or otherwise disposed of, if found straying in areas where cat management officers have authority to exercise their powers.’

It is so important that we understand the intent of John’s actions. Just as the ‘GROAP’ (Get Rid of All Pines) story, in all its absurdist manifestations, was designed to educate the public about the damaging effects of an introduced plant, so with the cat story. Only it was something much more destructive than pine trees. Cats and their owners were possibly the number one cause of the shocking reductions and extinctions within Australia’s wildlife. This continent has the well-known and unenviable record of the worst extinction rate on the planet.

Ironically, John may have killed only one cat in his life, this being the unfortunate neighbour’s cat he shot as a child. John expresses it comically, thus, ‘There wouldn’t be many people in the world who have killed less cats than me!’

Yet to this day, there are many who see the stunt as an end in itself. As the action of a cat-hater rather than the action of someone who loved wildlife. John puts it succinctly, thus, ‘Wherever I went I was asked to tell the latest cat joke. There is no doubt that we got more mileage out of cats than we ever got out of wildlife. That is a measure of the problem. Why do Australians think so little of their wildlife?’

John has never resiled from his action on that night of the awards. His emails carry the famous image. If that is how people choose to remember him, at least it means the message is still getting through, even if subliminally.